Quantum computing with superconducting qubits

We have seen in the last lesson the possibilities of quantum computation with trapped ions. However, a second major platform are superconducting qubits. They the platform of choice of commercial giants like google, IBM or Rigetti. In this lesson, we will identify the existence of qubits in superconducting circuits, the different gates and the read-out. We will finish by a comparison in the computing performance of trapped ions and superconducting qubits.

The quantum LC-oscillator

As in the second lesson, we have to find the harmonic oscillator, but this time in electric circuits. Then we can discuss the need of the Josephson junction for the implementation of superconducting qubits.

The fundamental ingredient for superconducting qubits are LC oscillators, which are simply put a loop of wire which is not closed. To study its quantum behavior we will closely follow the discussion in Sec. II of “A Quantum Engineer’s Guide to Superconducting Qubits”.

In electrical engineering we first have to identify the conjugate variables within the circuit. We will therefore follow the standard procedure of:

- Identifying the equations of motion.

- Identify the Lagrangien.

- Identify the conjugate variables.

- Write down the Hamiltonian.

- Quantize the Hamiltonian.

While it might be overly complicated for simple LC circuits it provides a powerful framework for more complex systems (see Nigg et al.)

Lagrangien formulation

The wire is caracterized by an inductivity, which is counteracting the change in current:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

This now leads to the Lagrangien:

![]()

Quantization

We can now identify the conjugate momentum the flux as:

![]()

We can now write down the Hamiltonian as:

![]()

At this stage we can quantize the system through the commutation relation:

![]()

So it is once again a harmonic oscillator with resonance frequency

![]() and ‘mass’

and ‘mass’ ![]() . So the system reads:

. So the system reads:

![]()

While this is now a quantum system, it is manifestly not a qubit as the

transitions are equidistant in energy with ![]() . The typical order

of magnitude is here 3-6GHz.

. The typical order

of magnitude is here 3-6GHz.

To prepare for the introduction of superconducting elements, we typically rewrite the equations above in terms of dimensionless quantities. Namely the Cooper pair density ![]() and the reduced flux

and the reduced flux ![]() with

with ![]() . These two quantities correspond directly to the density and the phase of the superconducting wavefunction that we will discuss in the next section. We then obtain the Hamiltonian

. These two quantities correspond directly to the density and the phase of the superconducting wavefunction that we will discuss in the next section. We then obtain the Hamiltonian

![]()

is the energy required to add a cooper pair.

is the energy required to add a cooper pair. is the inductive energy

is the inductive energy

The Josephson junction

To resolve the degeneracy we need to make the oscillator anharmonic. This is done through Josephson junctions, which are the backbone of superconducting electronics (very much like the transistor or the diode are classical electronics). To understand them roughly, we will fall back on the Feynman picture of Josephson dynamics.

A simplistic picture of superconductivity

We could spend several lectures to understand the physics of Josephson junctions in all its gory details. A good overview might be found in the following books (D.R. Tilley, 1990; Tinkham, 2004). However, the basic idea is that the fermionic electrons form cooper pairs at very low temperatures. These pairs are bosonic and can hence condense into a macroscopic wavefunction:

![]()

- the density is given by

.

. - The velocity is set by the gradient of the phase

.

. - The voltage is set by the time evolution of the phase

.

.

The Josephson relations

A Josephson junction describes now a system where two superconducting regions are slightly separated by a normal metal such that only tunneling is allowed between the two regions.

We can now write down the Schrödinger equation for this setup:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Single qubit control

Superconducting qubits can be controlled either through inductive or capacitive coupling. Inductive coupling is widely used for flux-qubits like the rf-squid. However, here we focus on the transmon qubit, which is typically capacitavely coupled

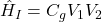

Going through the quantization procedure we discussed above, we can write the circuit Hamiltonian as:

![]()

The second part of the Hamiltonian resembles strong the electric dipole coupling we discussed in the last lecture. It contains the displaced charge, which is linearly coupled to an oscillating electric field. So we can rewrite the charge once again in terms of raising an lower operators and arrive at the coupled Hamiltonian:

![]()

All the other discussions are equivalent to our discussion on the ion and any other single qubit system.

Generating entanglement

Having identified the qubit, we can now also implement the entanglement gate to build the universal quantum computer. Different options exist:

- The qubit island could be coupled through a mutual capacitance, such that

.

. - The qubit island could be coupled through a mututal inductance, such that

.

.

Typically the inductive coupling is chosen in a regime of very small

coupling ![]() , where the

, where the ![]() describe the transmon

qubits. The full Hamiltonian reads then:

describe the transmon

qubits. The full Hamiltonian reads then:

![]()

we identified here ![]() . We can now further rewrite

the occupation in terms of raising and lowering operators

. We can now further rewrite

the occupation in terms of raising and lowering operators

![]() , which is can be expressed as a Pauli matrix for

the buttom manifold. So we actually have the coupling:

, which is can be expressed as a Pauli matrix for

the buttom manifold. So we actually have the coupling:

![]()

While this basic operating principle of capacitive coupling is indeed widely used, it is worth to read the fine-print as the different actual implementation can to different 2-Qubit gates:

- The iSWAP gate is the implementation of the

coupling.

coupling. - The phase gate, shows very high fidelities, but makes it necessary to tune the freuqency of the qubit. It implements a

-coupling on the spins. Fidelities of > 99% were demonstrated for this gate (Barends et al., 2014).

-coupling on the spins. Fidelities of > 99% were demonstrated for this gate (Barends et al., 2014). - The cross-resonance (CR) gate is only controlled through microwaves. It implements the a

-coupling on the spins. This is gate employed by IBM (Chow et al., 2011).

-coupling on the spins. This is gate employed by IBM (Chow et al., 2011).

A CNOT gate constructed from the physical entangling gates

We would now like to discuss how we can use the capacitive coupling to implement a CNOT gates. This discussion is closely related to the possibility of using a Soerensen-Molmer gate, discussed in lecture 2, to implement a CNOT gate.

The ![]() coupling for the right amount of leads to a

coupling for the right amount of leads to a

coupling matrix:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[iSWAP &= \left(\begin{array}{cccc}1 & 0 & 0 & 0\\0 & 0 &-i & 0\\0 & -i & 0 & 0\\0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{array}\right)\]](https://alqor.io/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-f47a57264da4a84158dfe11fc7388503_l3.png)

The iSWAP can then be used to represent the CNOT gate.

So we will focus shortly on the current limitations of qubit systems. Please be aware that this is a rapidly evolving field, so most likely the paragraph will be outdated within a few months. One good summary can be found in (Linke et al., 2017) and written by an ion trapping group.

Summmary

In this lesson, we discussed how the two level system is implemented in superconducting devices and how they are coupled. This should give you a basic feeling for this widely used hardware platform and its limitations. In the next lesson, we will discuss cold atoms as a leading platform for quantum simulation.