The qubit or the two level system

In this first lesson we are going to discuss the two-level system, i.e. the qubit, as it is the simplest unit of quantum computing systems. We discuss on a physics level with Hamiltonians etc its static properties like level splitting and avoided crossings. Then we discuss dynamical processes like Rabi oscillations and their connection to the notation of quantum computation.

This lays the basis for the discussion of quantum computation hardware in the next lessons. Namely:

- trapped ions in lesson #3

- superconducting qubits in lesson #4

- cold atoms in lesson #5

Hamiltonian, Eigenstates and Matrix Notation for the qubit

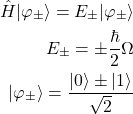

To start out, we will consider two eigenstates ![]() of the Hamiltonian

of the Hamiltonian ![]() with

with

(1) ![]()

Quite typically we might think of it as a two-level atom with states 0 and 1. The eigenstates can be expressed in matrix notation:

(2) ![]()

so that

![]()

If we would only prepare eigenstates the system would be rather boring. However, we typically have the ability to change the Hamiltonian by switching on and off laser or microwave fields. We can then write the Hamiltonian in its most general form as:

![]()

Sometimes we will also chose the definition:

(3) ![]()

It is particularly useful for the case in which the coupling is created by a laser. Another useful way of thinking about the two-level system is as a spin in a magnetic field. Let us remind us of the definitions of the of the spin-1/2 matrices:

![]()

We then obtain:

(4) ![]()

Case of no perturbation

This is exactly the case of no applied laser fields that we discussed previously. We simply removed the energy offset ![]() and pulled out the factor

and pulled out the factor ![]() , such that

, such that ![]() measures a frequency. So we have:

measures a frequency. So we have:

(5) ![]()

We typically call

Case of no detuning

Let us suppose that the diagonal elements are exactly zero. And for simplicity we will also keep ![]() as it simply complicates the calculations without adding much to the discussion at this stage. The Hamiltonian reads then:

as it simply complicates the calculations without adding much to the discussion at this stage. The Hamiltonian reads then:

![]()

Quite clearly the states ![]() are not the eigenstates of the system anymore. How should the system be described now ? We can once again diagonalize the system and write

are not the eigenstates of the system anymore. How should the system be described now ? We can once again diagonalize the system and write

(6)

Two important consequences can be understood from this result:

- The coupling of the two states shifts their energy by

. This is the idea of level repulsion.

. This is the idea of level repulsion. - The coupled states are a superposition of the initial states.

This is also a motivation the formulation of the ‘bare’ system for ![]() and the ‘dressed’ states for the coupled system.

and the ‘dressed’ states for the coupled system.

General case

Quite importantly we can solve the system completely even in the general case. By diagonalizing the Hamiltonian we obtain:

(7) ![]()

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

deltaMax = 5

delta = np.linspace(-deltaMax, deltaMax, 100)

omega = 1

Eplus = np.sqrt(delta**2+omega**2)/2

Eminus = -np.sqrt(delta**2+omega**2)/2

f, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(delta, Eplus, label="E_+")

ax.plot(delta, Eminus, label="E_+")

ax.legend()

ax.set_xlabel("detuning Delta")

ax.set_ylabel("energy E");

The Eigenstates then read:

(8) ![]()

where

(9) ![]()

Dynamical properties of the qubit

After the static case we now want to investigate the dynamical properties of the two-state system. We calculate the time evolution of ![]() with the Schrödinger equation and the perturbed Hamiltonian :

with the Schrödinger equation and the perturbed Hamiltonian :

![]()

![]()

We have two coupled differential equations and we luckily already know how to solve them as we have calculated the two eigenenergies in the previous section. For the state ![]() we get

we get

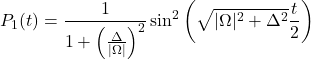

(10) ![]()

with the factors

(11) ![]()

As a first step, we have to apply the initial condition and express

(12) ![]()

By equating the coefficients we get for

(13) ![]()

One thus gets:

(14) ![]()

(15)

def rabi_osc(time: float, omega: float, delta: float) -> float:

"""

time evolution in the Rabi oscillation

Args:

time: time at which we measure

omega: coupling strength

delta: detuning

Returns:

float: probability to be in the excited state

"""

return 1/(1+(delta/omega)**2)*np.sin(np.sqrt(omega**2+delta**2)*time/2)**2

omega = 2*np.pi*1

time = np.linspace(0,2, 100)

delta = 0

f, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(time, rabi_osc(time, omega, 0), label = "Delta = 0")

ax.plot(time, rabi_osc(time, omega, omega), label = "Delta = Omega")

ax.plot(time, rabi_osc(time, omega, 10*omega), label = "Delta = 10cdotOmega")

ax.legend()

ax.set_xlabel("time t")

ax.set_ylabel("probability P_1")

A few key words concerning Rabi oscillations are in order:

- The probability to be in the excited state is indeed maximal if there is zero detuning.

- The speed of the oscillations get higher with higher detuning. This fact is often overlooked at first sight but key in approximations like the rotating wave approximation.

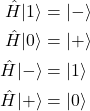

A few words on the quantum information notation

The qubit is THE basic ingredient of quantum computers. However, you will typically not find Pauli matrices and other common notations of two-state systems in the platforms. The typical notation there is:

is a rotation around the x-axis for an angle

is a rotation around the x-axis for an angle  .

.- Same holds for

and

and  .

.  denotes the rotation around the x axis for an angle

denotes the rotation around the x axis for an angle  . So it transforms

. So it transforms  into

into  and vise versa.

and vise versa. denotes the rotation around the x axis for an angle

denotes the rotation around the x axis for an angle  . So it transforms

. So it transforms  into

into  and vise versa.

and vise versa.

The most commonly used gate is actually one that we did not talk about at all, it is the Hadamard gate, which transforms ![]() into

into ![]() and

and ![]() into

into ![]() :

:

(16)

Summary

In this lesson we have seen the basic properties of qubits. For a much more detailed discussion we refer the reader to the nice qiskit textbook. We have seen how qubits are controlled through external fields and how the most common gates of quantum information are realized.

In the next lesson we will discuss the second important building block of quantum hardware, i..e the quantum harmonic oscillator. This lays the groundwork for more detailed discussions of different platforms in the next steps.